Basic Information

- Interdisciplinarity: Technology, Engineering, Computing

- Topic(s): Digitalisation / Green Deal

- Duration: 2 months

- Target Age Group: 12–14 years old

- Partners Involved: HU, Parents, Students, IT Experts

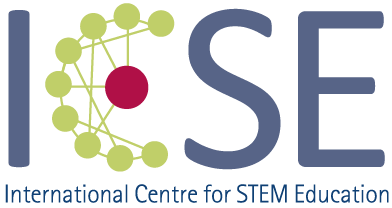

Picture: The design used for design purposes by the participants in the mini smart road project.

Summary

In this Open Schooling activity, students created a model system capable of detecting road slipperiness using sensor technology and Arduino. The goal was to simulate intelligent infrastructure that can alert drivers when the road is wet, helping to prevent accidents. Through this process, students examined topics such as digitalisation, sensor integration, and road safety. The activity involved students in all phases of the project cycle—from identifying the problem to presenting their final solutions—and was supported by mentors from the university.

Description of the implementation process of the activity

The implementation started with students discussing environmental and local safety concerns. After these discussions, the issue of accidents due to slippery roads became a clear and practical problem. The idea of developing a warning system was then conceived. During the preparation phase, students attended a brief introductory workshop on Arduino and sensor systems. A road model was built using cardboard or foam base materials.

Students programmed the Arduino microcontroller so that when the sensor was detected, a warning system would activate—either through a flashing LED or a buzzer. Throughout the ac certain threshotivity, students tested different moisture levels, modified their codes, and refined their physical designs. Code support and troubleshooting were aided by ChatGPT, helping students debug and understand the logic behind their programmes. The project culminated in a school-wide demonstration event where students presented their working models to teachers, peers, and families.

Strategies to win schools

To engage schools, existing networks and prior collaborations between university staff and science teachers were leveraged. Teachers were informed about how the activity alignsurriculum objectives and promotes digital skills with national c. Additionally, the activity was presented as anunity, which encouraged participation. The prosp innovative STEM learning opportect of project visibility through university events and support in the form of materials also played a significant role. The opportunity to participate in dissemination events such as science days or fairs further attracted school interest.

Schools support

During implementation, comprehensive support was provided to schools. All necessary materials, including Arduino kits, sensors, and other electronics, were supplied by the university. Prior to the project launch, teachers were invited to a short training and orientation session. Continuous mentoring was offered via email and online video meetings to ensure that teachers and students could ask questions and receive feedback. Examples of working code were shared, and guidance on using digital tools, such as ChatGPT, was provided to assist with programming. Support was also extended for the final presentation phase through printed posters and visual aids.

Key-success factors

One of the key success factors was the relevance of the problem to students’ local contexts, which increased engagement and motivation. The tangible application of science and technology helped students understand how digital tools can be used to solve real-world challenges. Involving students in every step of the process—ideation, coding, assembling, testing, and presenting—enabled deeper learning. The collaboration between schools and university mentors was vital in ensuring quality guidance and sustained momentum. Additionally, the use of AI-based support tools like ChatGPT allowed students to troubleshoot and comprehend coding logic more effectively, which improved the quality of the final outcomes.

Challenges

Several challenges emerged during implementation. Initially, many students were unfamiliar with Arduino or electronics, which slowed down the early phases. Writing the code and configuring sensor thresholds involved a steep learning curve, and some technical difficulties arose regarding sensor placement and signal stability.

These challenges were addressed through targeted support. The mentoring team simplified the initial code structures and provided students with structured templates. Collaborative group work helped distribute tasks and leverage peer learning. The technical issues with sensor positioning were resolved through iterative testing and teacher supervision. Furthermore, using ChatGPT to assist with programming and debugging proved especially helpful in resolving logical errors efficiently.

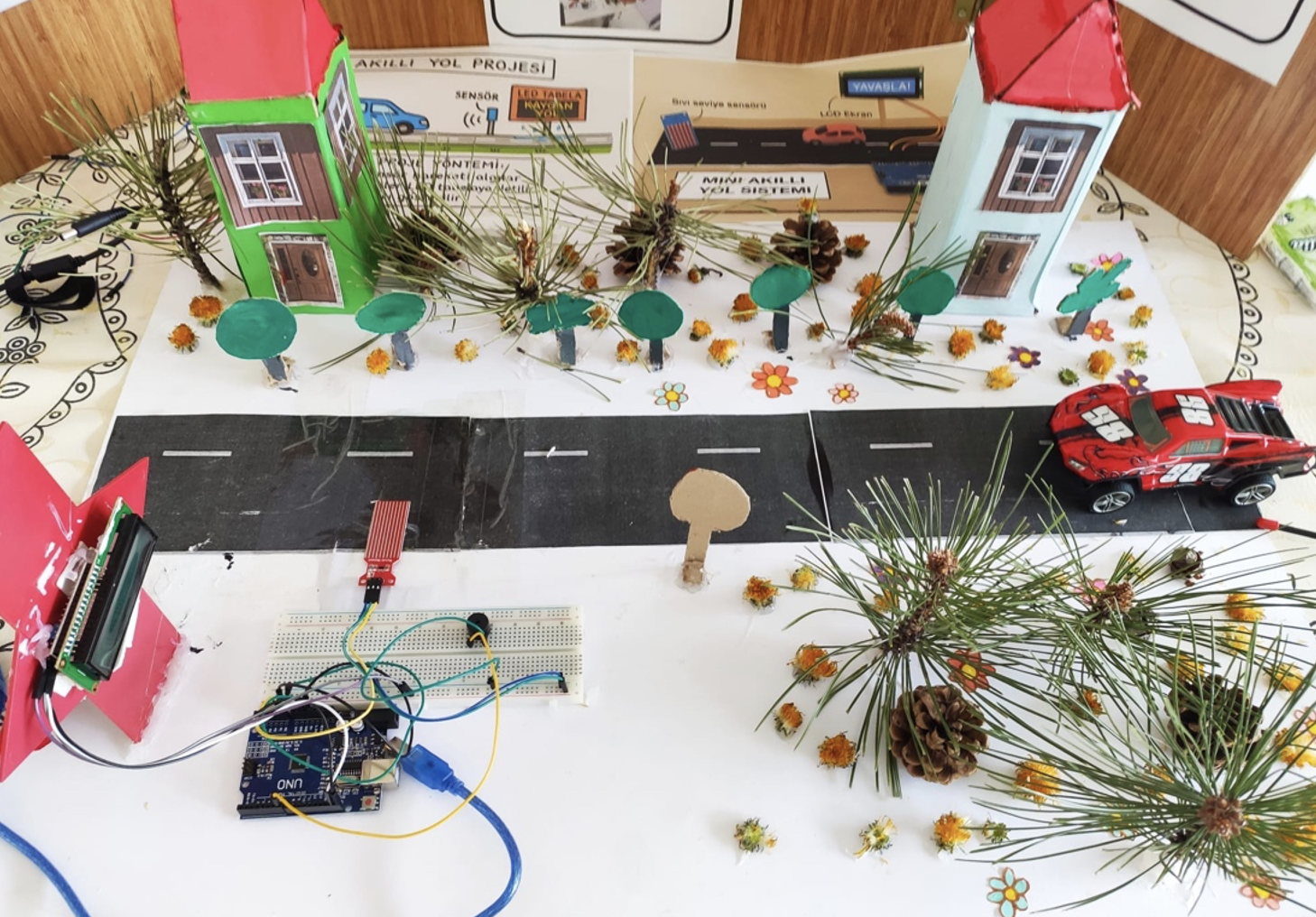

Picture: A prototype of the project made by students.

Outcomes

Student feedback showed a clear increase in interest in science and engineering. Several students expressed surprise at how coding could directly influence real-life situations. Teachers reported higher levels of student participation and enthusiasm. Parents valued the practical focus and appreciated the chance to see their children’s work during theThe project was featured on the sharing event. school website and in local newspapers. As a next step, a more advanced version involving renewable energy is being considered by the students and teachers involved.

Reflective remarks

This activity provided students with a hands-on experience in applying scientific knowledge to solve local issues. It successfully demonstrated how Open Schooling can integrate real-world relevance, technology, and community awareness. The activity showed strong potential for replication in other schools and communities. It highlighted the importance of planning teacher training and scaffolding complex technical content into age-appropriate formats. Future implementations could expand the project by integrating additional environmental sensors (e.g., temperature, humidity) or solar-powered systems. Sustainable impacts may be achieved by embedding such projects within the broader science curriculum and establishing longer-term school-university partnerships.

Additional materials

Coding generated using AI for Arduino micro controls:

//Su seviyesini LCD Ekranda gösterme

#include <LiquidCrystal_I2C.h>

LiquidCrystal_I2C lcd(0x27,16,2);

int seviye = 0;

int buzzer = 7;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

lcd.begin();

pinMode(buzzer, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

Serial.print(“Su Seviyesi Değeri: “);

Serial.println(seviye);

seviye = analogRead(A0);

if (seviye<=350)

{

lcd.clear();

lcd.setCursor(0,0);

lcd.print(“Yol guvenli”);

lcd.setCursor(0,1);

lcd.print(“Devam et”);

}

if (seviye>351 && seviye<=450)

{

lcd.clear();

lcd.setCursor(0,0);

lcd.print(“Zemin islak”);

lcd.setCursor(0,1);

lcd.print(“Dikkat Et”);

}

if (seviye>451 && seviye<=500)

{

lcd.clear();

lcd.setCursor(0,0);

lcd.print (“cok Su var”);

lcd.setCursor(0,1);

lcd.print (“Hizi azalt”);

}

if (seviye>501)

{

lcd.clear();

lcd.setCursor(0,0);

lcd.print (“Sel seviyesi”);

lcd.setCursor(0,1);

lcd.print(“Dur”);

}

if (seviye>501)

{

digitalWrite(buzzer, HIGH);

delay(100);

digitalWrite(buzzer, LOW);

delay(100);

}

delay(1000);

}